1994–the present

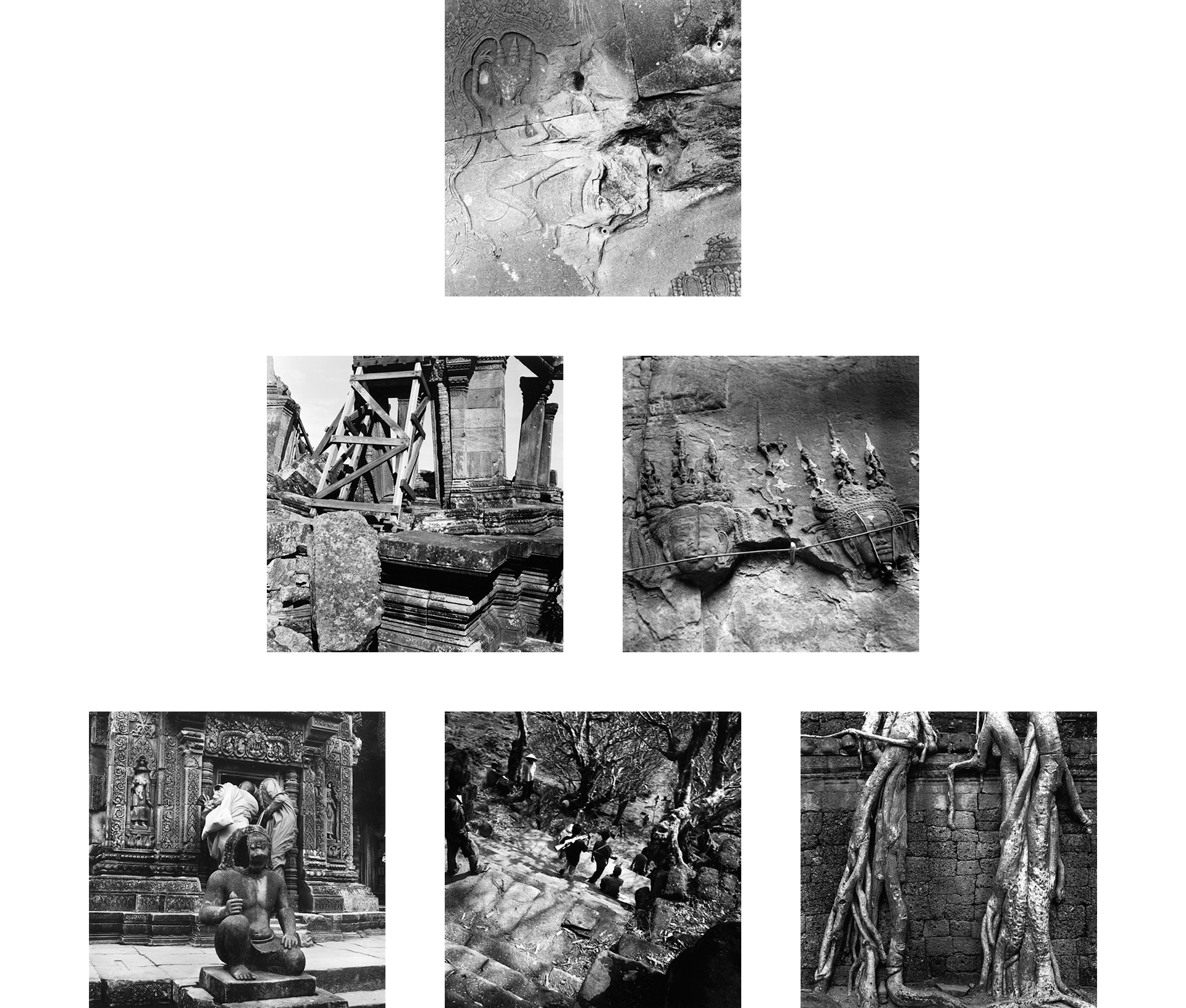

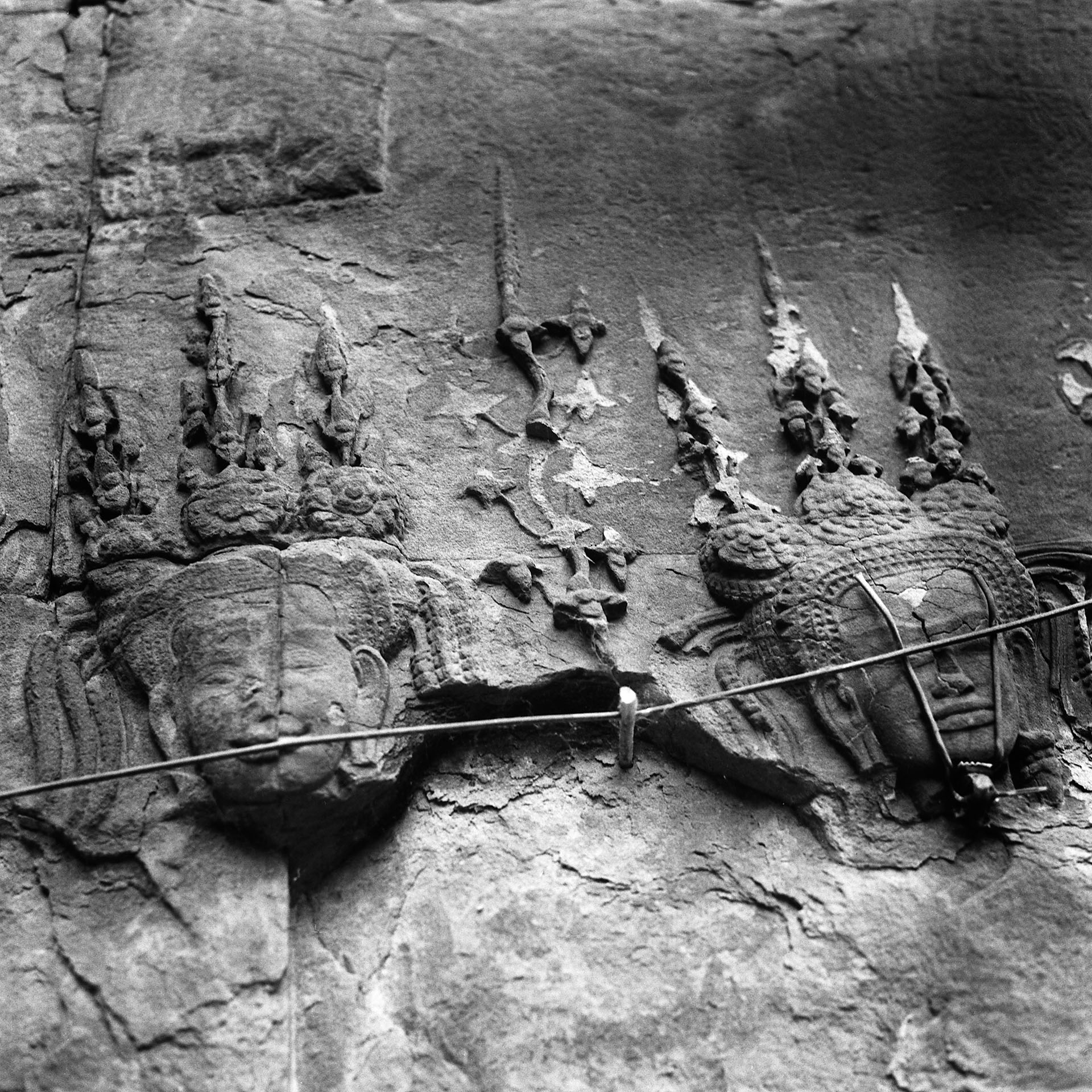

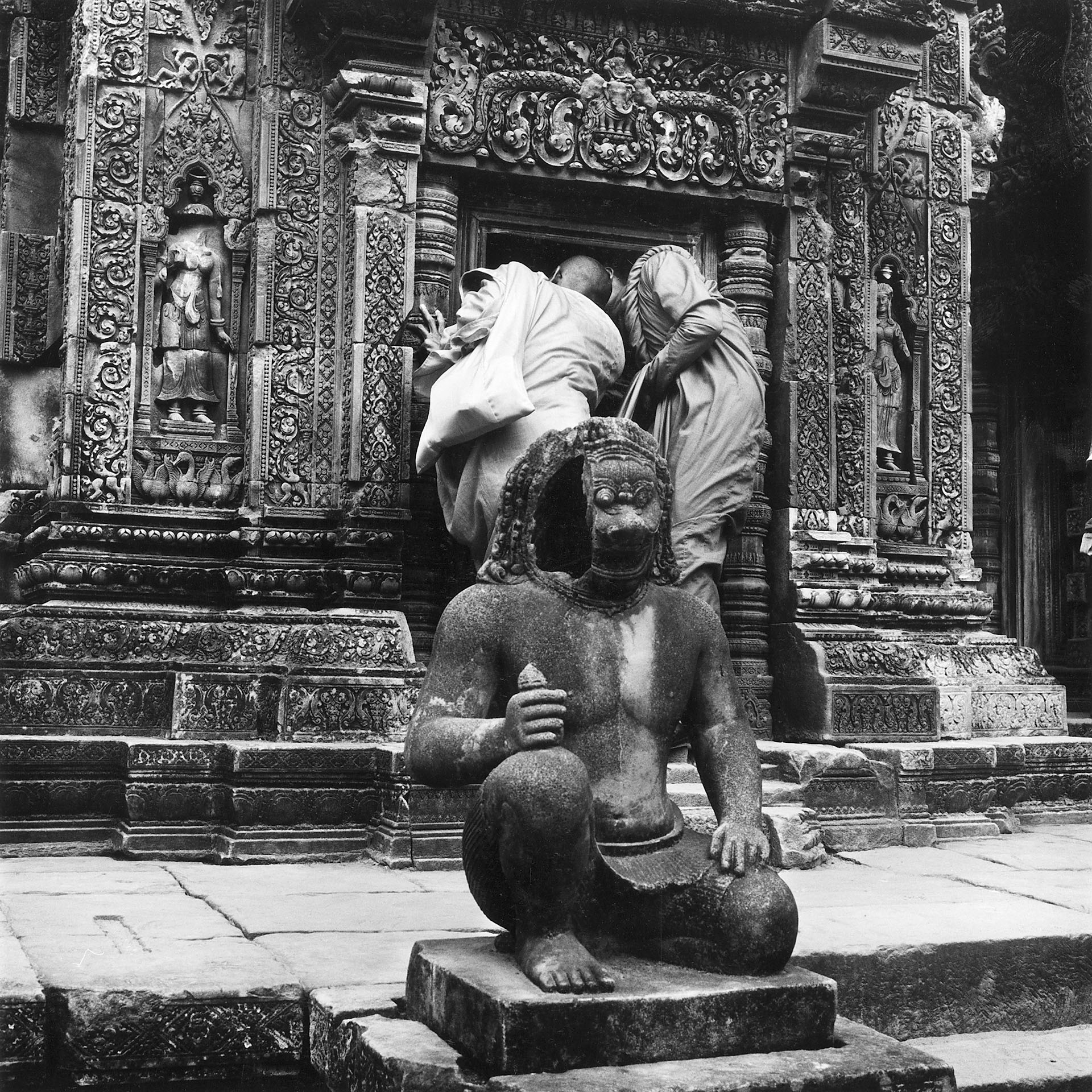

Angkor – The Mercy of Ruins

“No coffins are used for the dead in Cambodia; they are laid out on straw matting and covered by cloth. In funerary processions these people, like ourselves, are seen off with flags, banners, and music. The mourners take two platters of fried rice and scatter it by the handful along the way. They carry the corpse outside the city to some lonely place, abandon it there, and after reassuring themselves that the vultures, dogs, and other beasts have arrived to devour it, return home…”

This was but one of the “ways of these barbarians” observed by Chou Ta-Kuan, the Chinese emissary dispatched to the court of the Khmer by Kublai Khan in 1296. Gone were the days of the Khmer empire’s greatest monarch Jayavarman VII, architect of many of Angkors greatest sandstone monuments. Hinayanist Buddhism preached simplicity, poverty, and a sort of spiritual democracy.

More than six and a half centuries later the Khmer Rouge emerged from the Cambodian civil war, which was itself a sideshow of the American war in Vietnam. They sought not only to assert an identity that embodied the accomplishments of history, but also to create a new society more glorious than Angkor. Based on collective mobilization and driven by the vision of absolute self-sufficiency, their agricultural reforms and large-scale social engineering and hydraulic projects in fact led only to famine and genocide.

By then the Angkor region had become a battlefield, which it remained until the early 1990s, when it became a safe haven for internally displaced people whom the UN mission had been unable to protect. Two decades of interdisciplinary research and (recently Lidar-assisted) archaeology have since revealed what the jungle, until now, had obscured: a vast urban landscape of successive capitals laid out around temple-mountains, with gridded streets, a network of canals for irrigation and transportation, and bridges. This was the backdrop of Chou Ta-Kuan’s observations: the vestiges of a civilization which due to the combined factors of climate change, soil erosion, and deforestation caused by intensive rice cultivation, expired over the course of a century.

The AK47s to be heard during nights spent in the towers of Angkor Wat at last fell silent when, in the mid-1990s, peace finally came. But with the gunfire died the whisper of fortune-tellers, and the sound of the bamboo flute, and the three-stringed zither played by the blind and the maimed on the causeways, and in the courtyards and galleries of the temples. Having once been places of worship, the monuments were increasingly converted into sights.

Reportages, complementing personal work, were commissioned and published by Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich.

Group exhibition

Modena per la Fotografia (Birmania. Cambogia: Il mondo, la carne, il diavolo), Modena 1995

Assignments

- 2010–2018Afghanistan – Glacier Walks in Times of War

- 2012Burma Revisited

- 2009Swat – Mutilated Faces

- 2007Kazakhstan – Oil Great Game in Central Asia

- 2005Turkmenistan – A Journey under Surveillance

- 2004China – Farewell to Kashgar

- 2001–2010Afghanistan – A Thirty Years War

- 2001China – The Transformation of Xinjiang

- 2001Afghanistan – Drought and Famine

- 2000Kashmir – Paradise Lost

- 2000Ulanbataar – Children’s Underworld

- 2000London – Going Southwark

- 1999Indonesia – East Timor: Times of Agony

- 1998–1999Borneo – Destruction Business

- 1998Afghanistan – Economy of Survival

- 1997Cambodia – Quiet Days in Pailin

- 1996Tajikistan – Forbidden Badakshan

- 1995Iran – Roads to Isfahan

- 1994–the presentAngkor – The Mercy of Ruins

- 1994Bangladesh – Sandwip: An Island disappears into the Sea

- 1993Calcutta – Durga Puja

- 1992–1996Indochina – Legacies of War

- 1992Cambodia – Resurrecting a Country

- 1991–1992Burma – Behind the Bamboo Curtain

- 1990Ahmedabad – Cotton Mills

- 1987China – The Pulse of the Earth

- 1978–1980Greece – Lavrion Silver