1977–the present

Faces

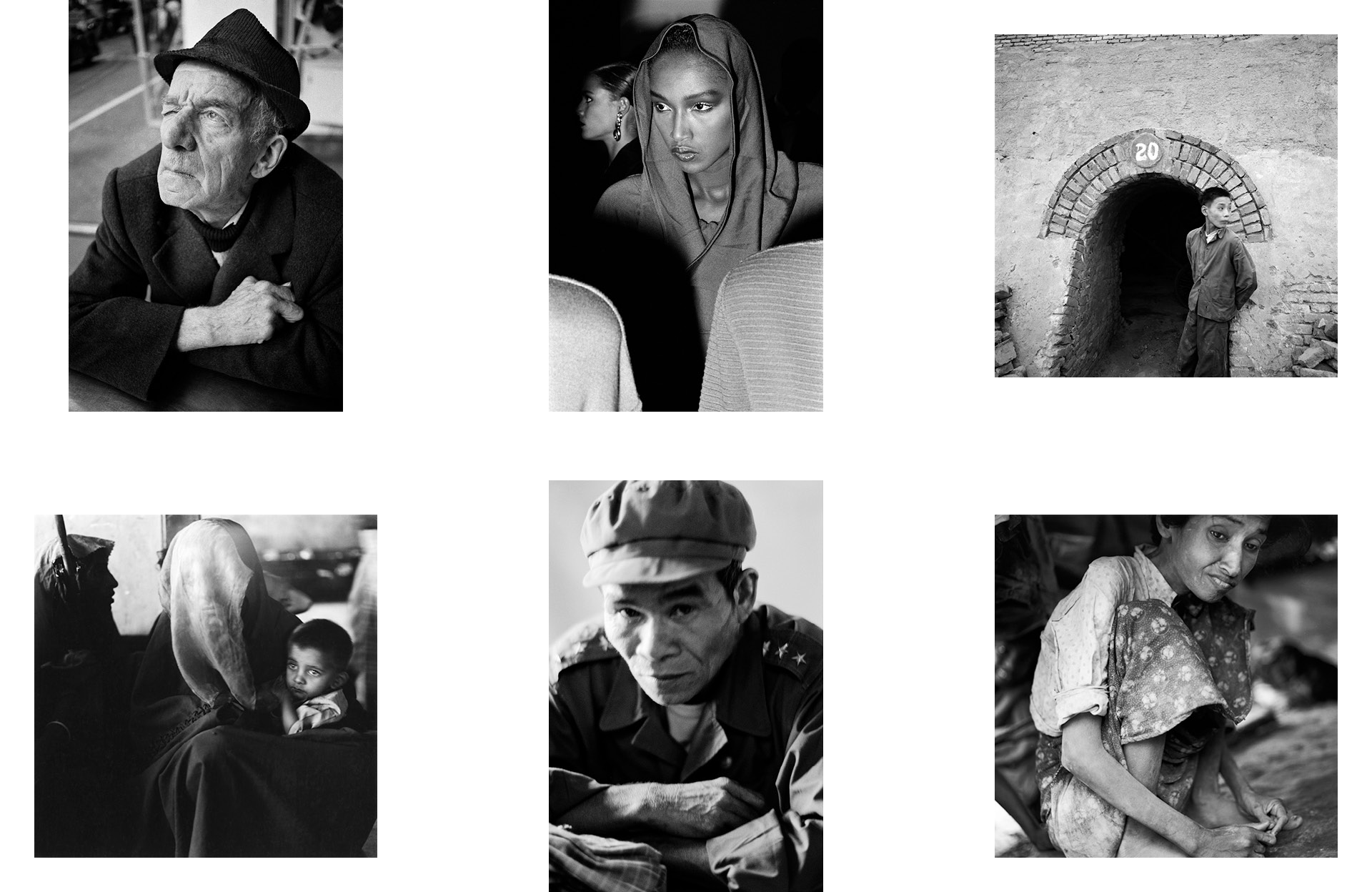

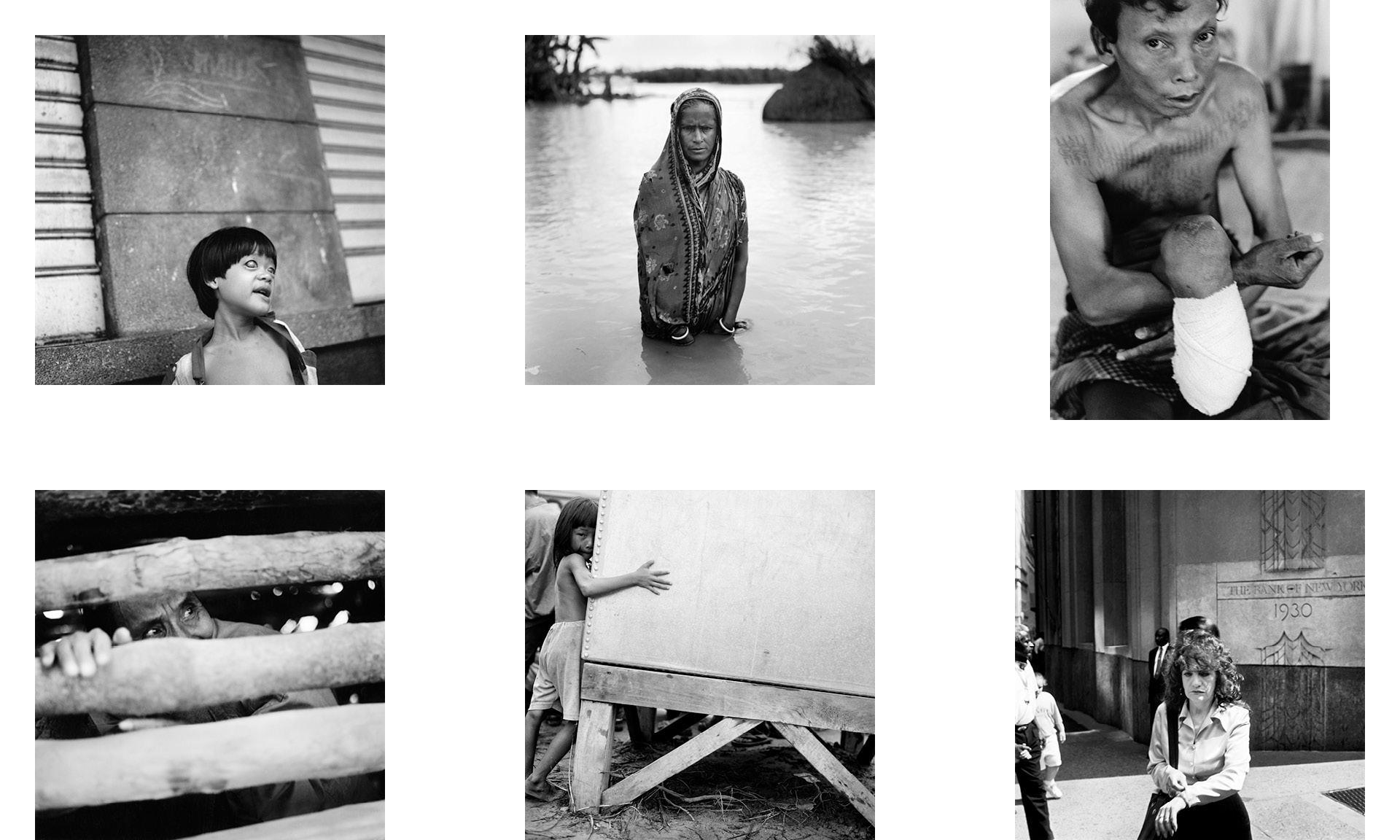

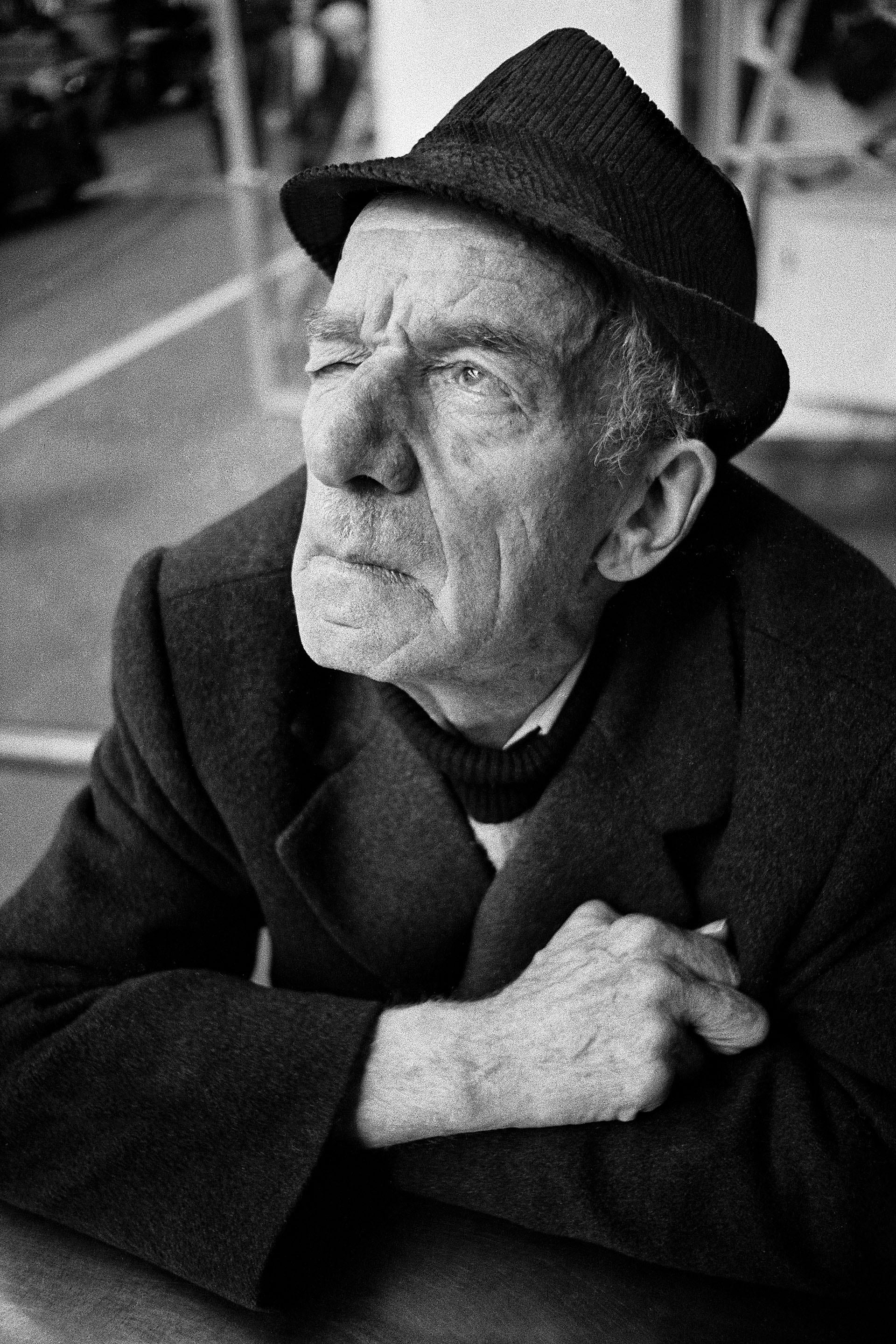

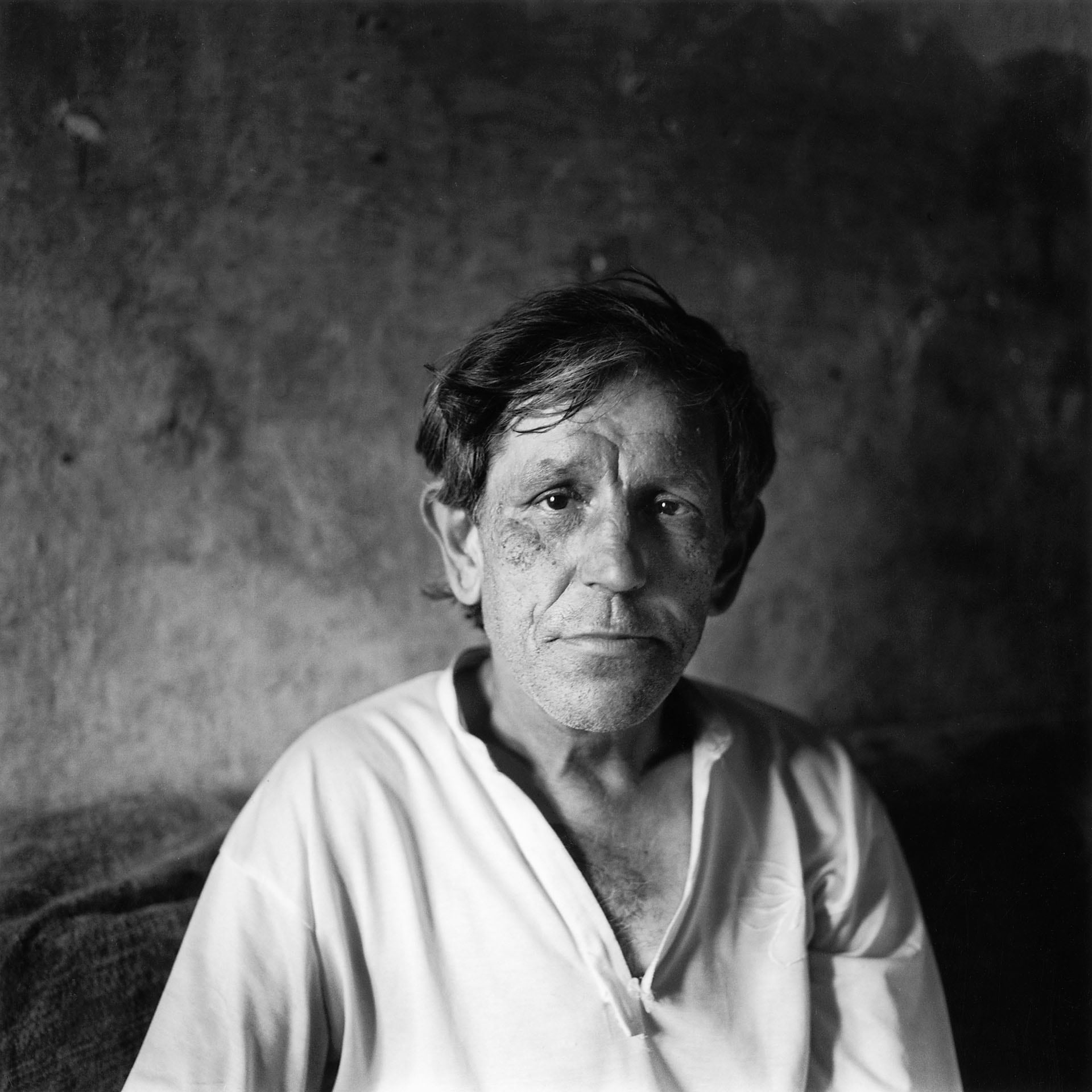

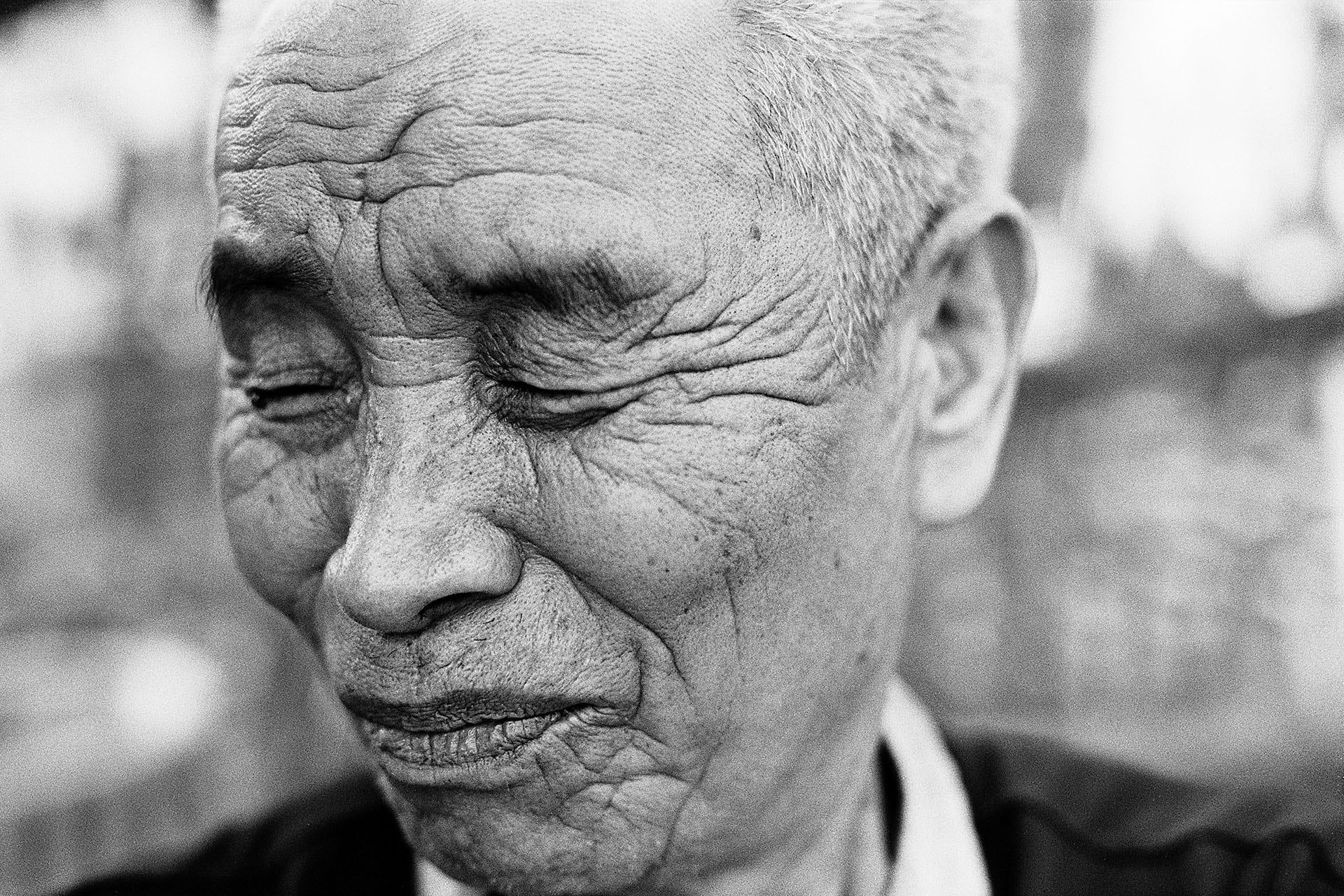

I am not known as a photographer of portraits, although I have taken a few – whether chance encounters or, mostly, as part of a story either at home or on location. As it happened, some of my sitters – e.g. John Cage, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, my grandmother – passed away soon after I had photographed them. This may have been the destiny of others too, without my knowing it. After all, obituaries are not a priority in war and calamity, especially when the deceased’s achievements belong in a domain other than that of the minority generating or deserving public interest.

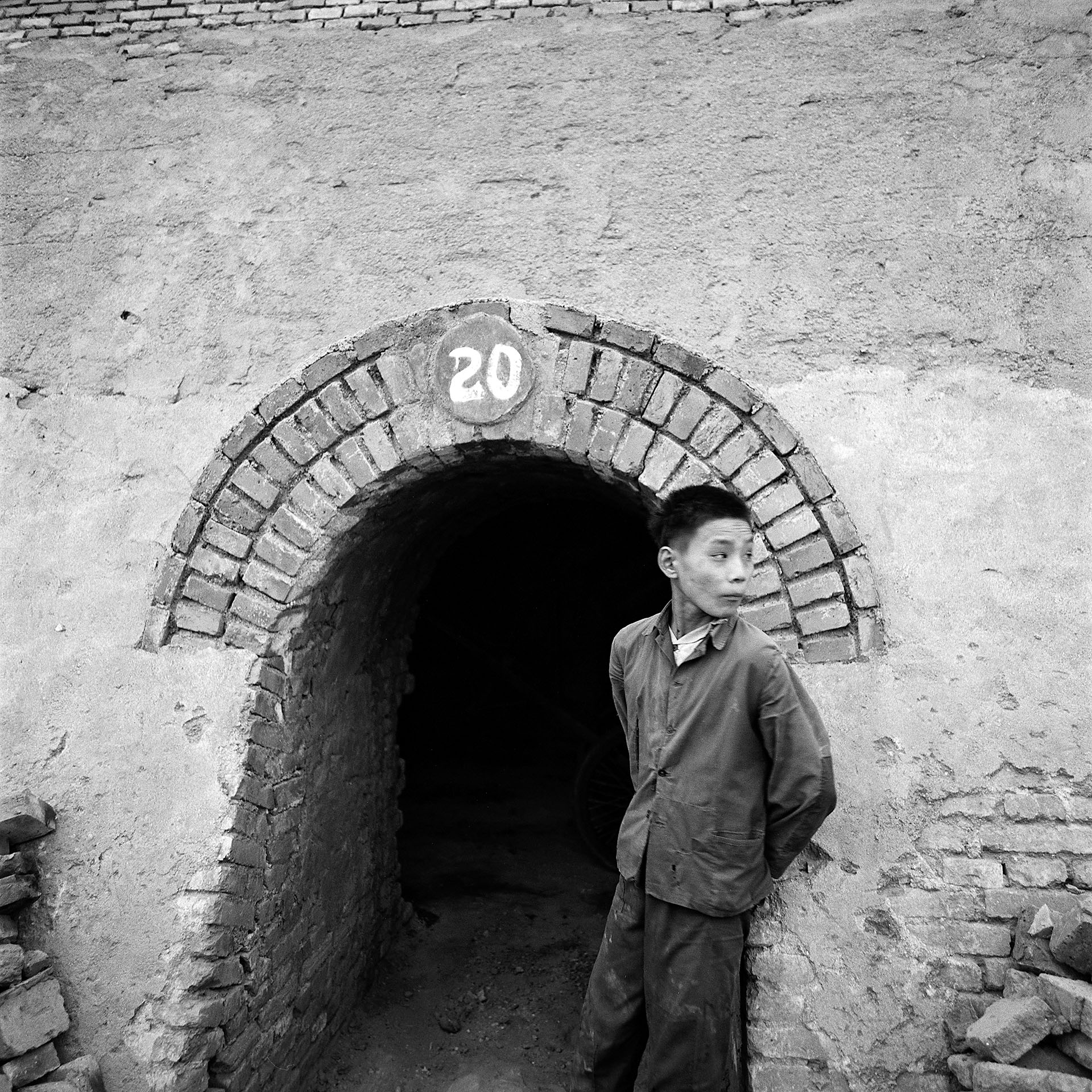

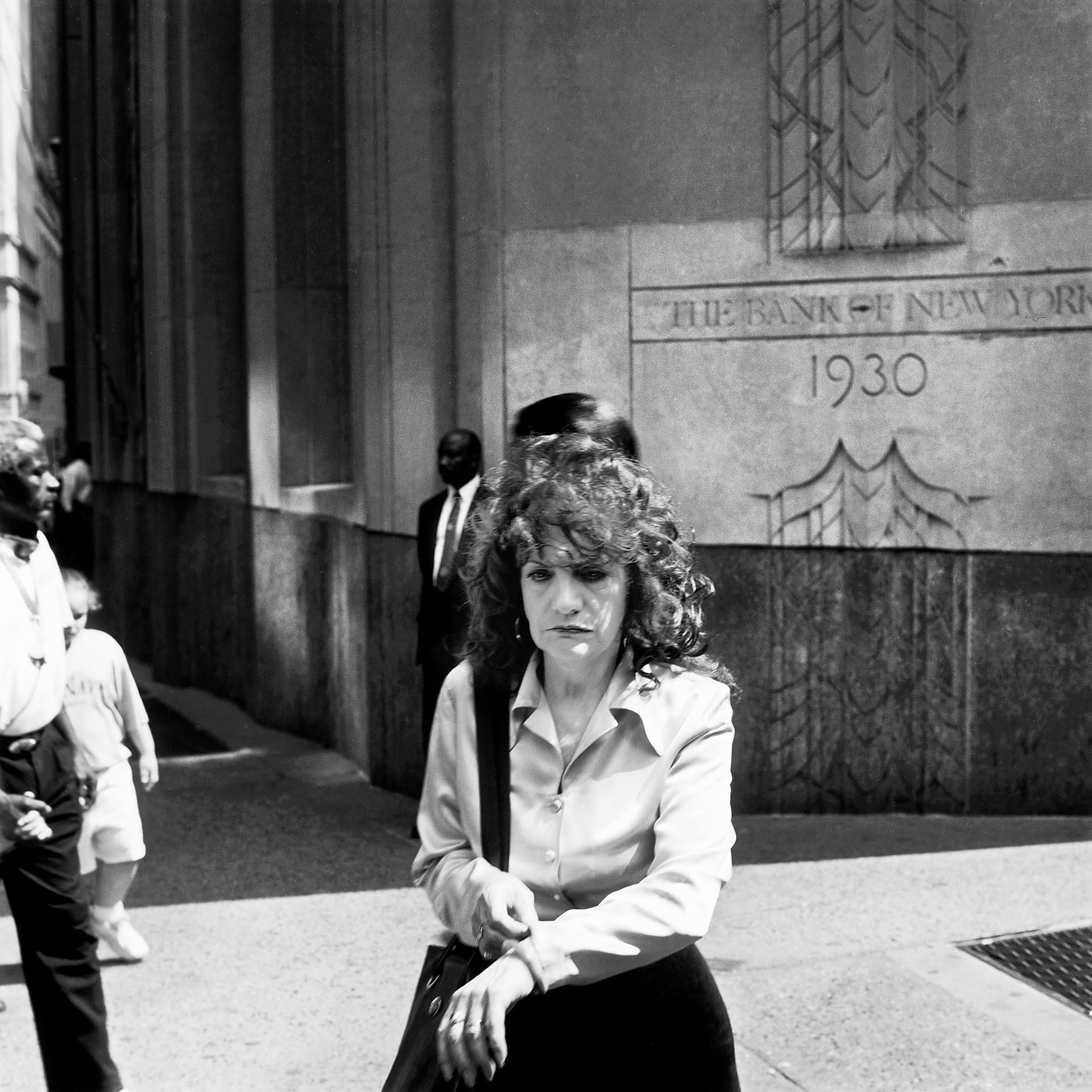

Photography, owing its existence to time, also annihilates time by arresting a motion. Whether it is a step, a kiss, a fall, a breath – the moment is ripped from the continuum. In the photograph, the mouth does not articulate any objection, the hand does not become a fist. Taking a portrait of a person facing the camera remains a kind of theft, even when there is consent, And handing back an image does not reverse the action, just as the photograph of one deceased does not awaken that person to life.

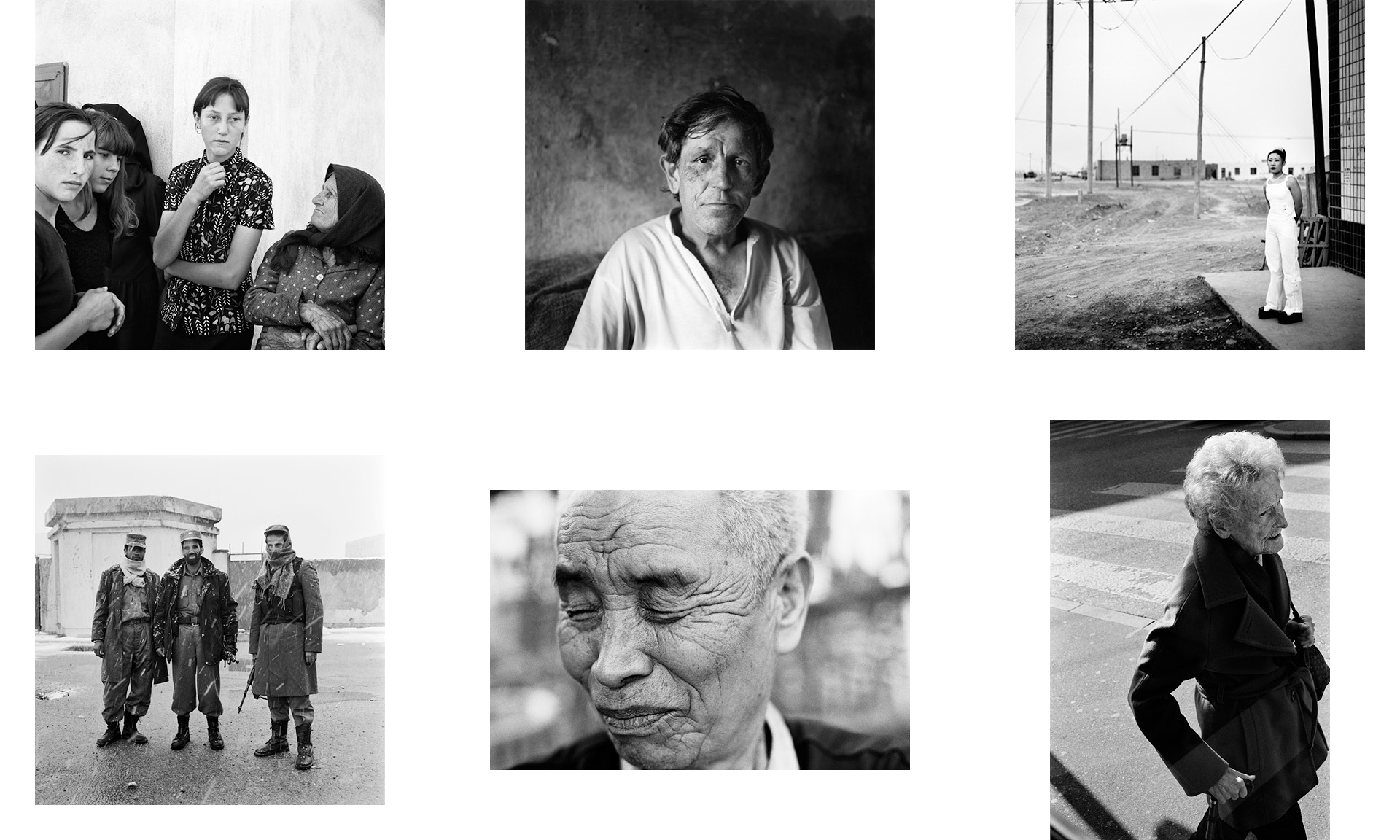

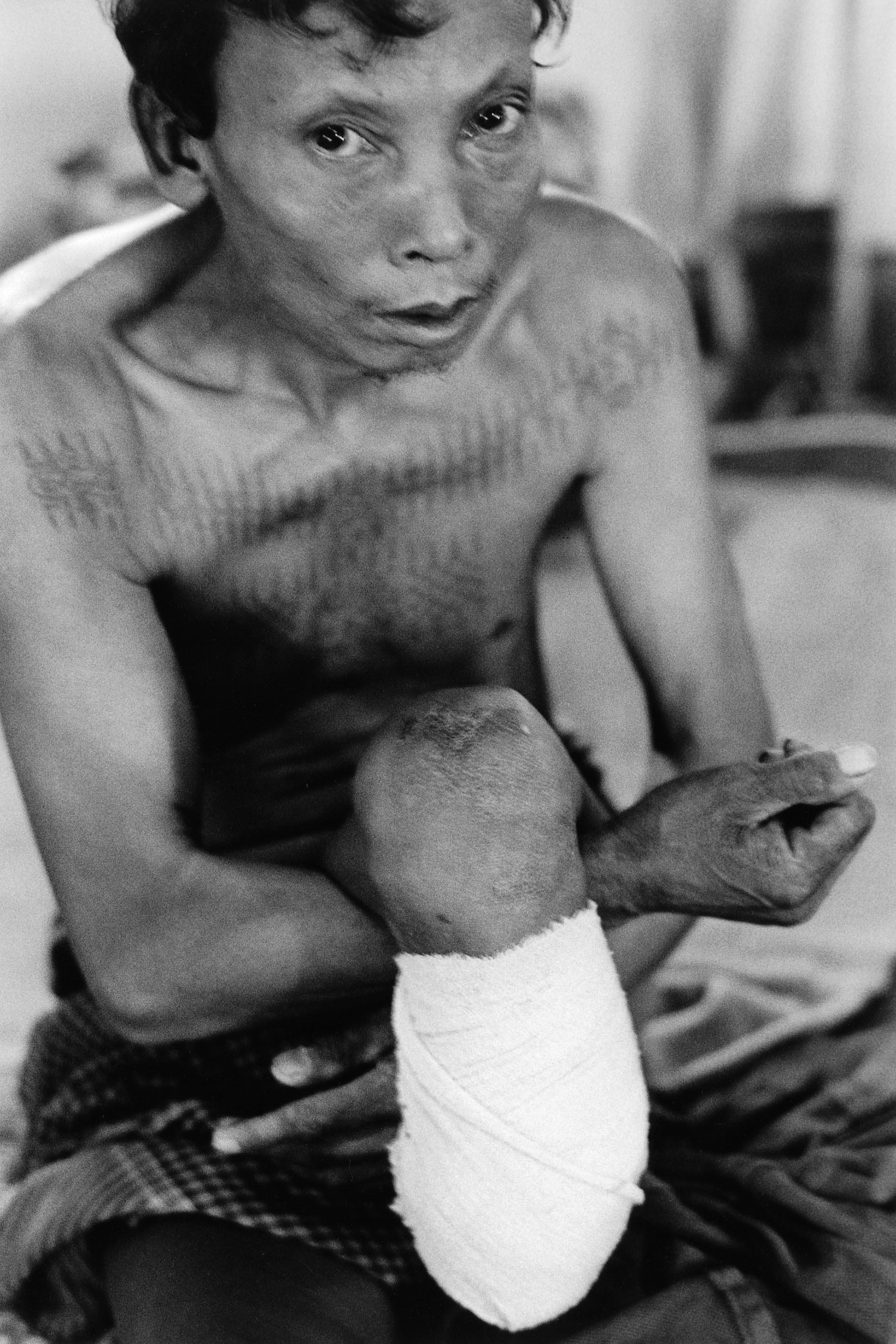

Sometimes one has a duty as a photographer. The children in the Rohingya refugee camp had moved aside to let the man approach me, and when he stopped at arm’s length before the camera, they closed in again. The man was very old, emaciated, and bent over, but he was holding firmly to a stick. He looked up at me with rheumy eyes that did not blink but summoned me: “Take my picture.” The light was wrong (contre-lumière so that his dark skin was further obscured by the glare) as was the whole situation (in the background the kids had resorted to Rambo gestures), but the moment was right. I took one picture and on hearing the shutter, the man turned around and walked away. He knew that as of now there was visual proof of his existence. Whether it was in his or in my world didn’t matter.

En Route

- 1987–the presentEntanglements

- 1977–the presentFaces

- 1991Iran – Kurdish Exodus

- 1990Georgia – Journey Through the End of an Era

- 1989Istanbul – Tanneries

- 1987China – Between the Walls

- 1987China – Undermining Buddha

- 1986Prague – Sentimental Journey

- 1986Egypt – Small Tour

- 1986–2010Zurich – Brief Encounters

- 1982–1986Silhouettes and Accessories

- 1977–1980Formation

- 1972–1976First Exposures